Solving Complex Data Challenges for Private Markets

Charles River for Private Markets is an investment management solution for institutions investing in Private Credit, Private Equity, Real Estate, Infrastructure, and Funds. Our cloud-based technology solution helps investors who need both flexibility and centralization for their investment data.

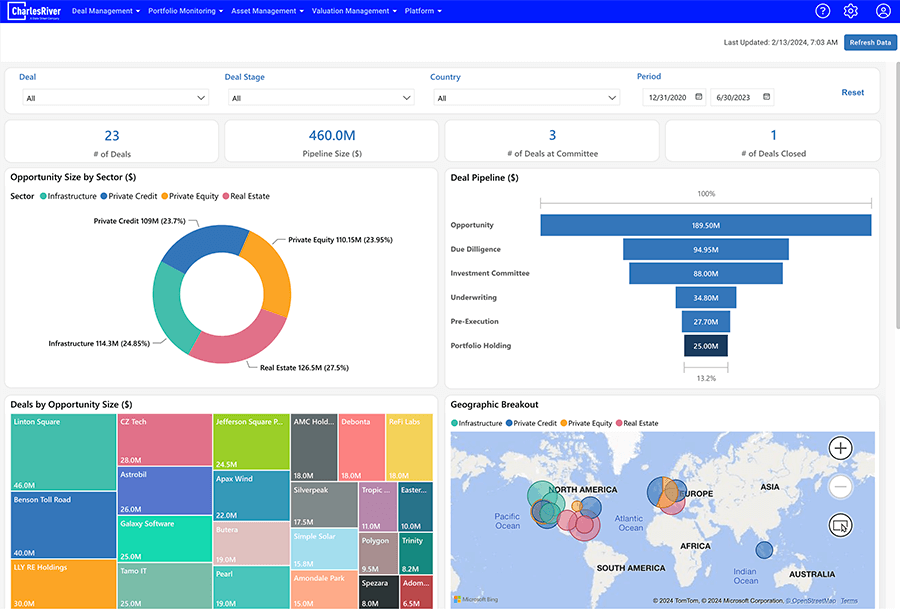

Private Market investment data is notoriously opaque, often living in disparate spreadsheets and disconnected technology point solutions. Managing it can take significant resources and extracting the necessary insights for investment decisions is often time-consuming and error prone.

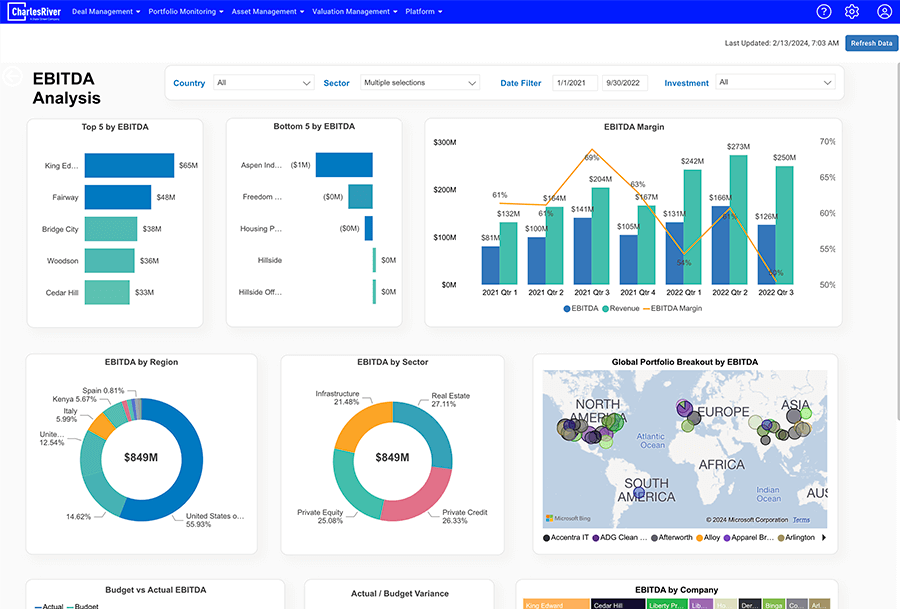

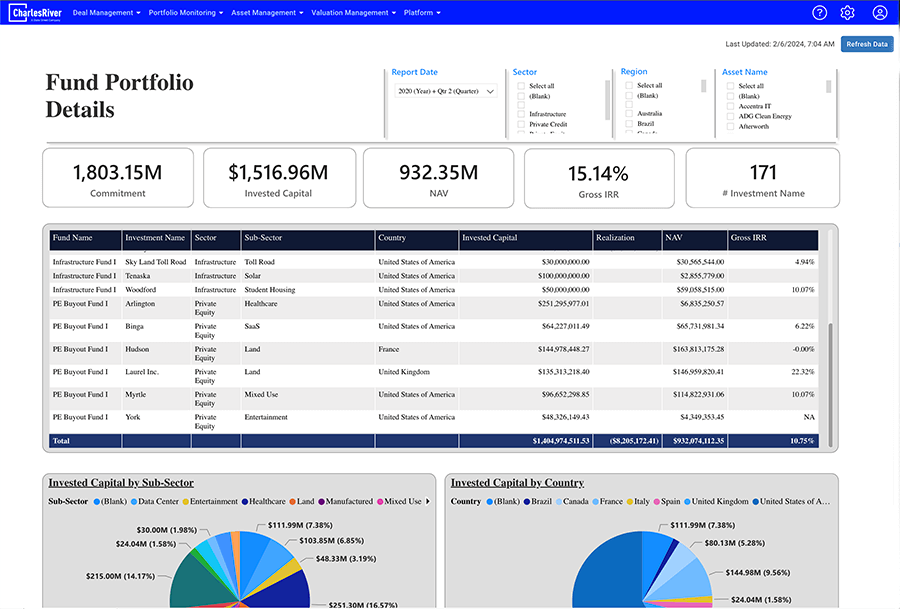

Charles River for Private Markets brings all your data together, giving you transparency and data quality from the fund level down to the asset level. It seamlessly connects your data, people, and processes, helping you scale your operations more efficiently. Our frameworks solve data challenges in Deal Management, Portfolio Monitoring, Asset and ESG Management, and Valuation Management.

Why Clients Choose Us

Scale

An investment management solution to help grow your operations

Agility

Asset-level up & multi-sector flexibility and best practices

Resiliency

Oversight of key investment functions such as investment analysis, valuations, and scenarios

Public to Private: Total Portfolio View

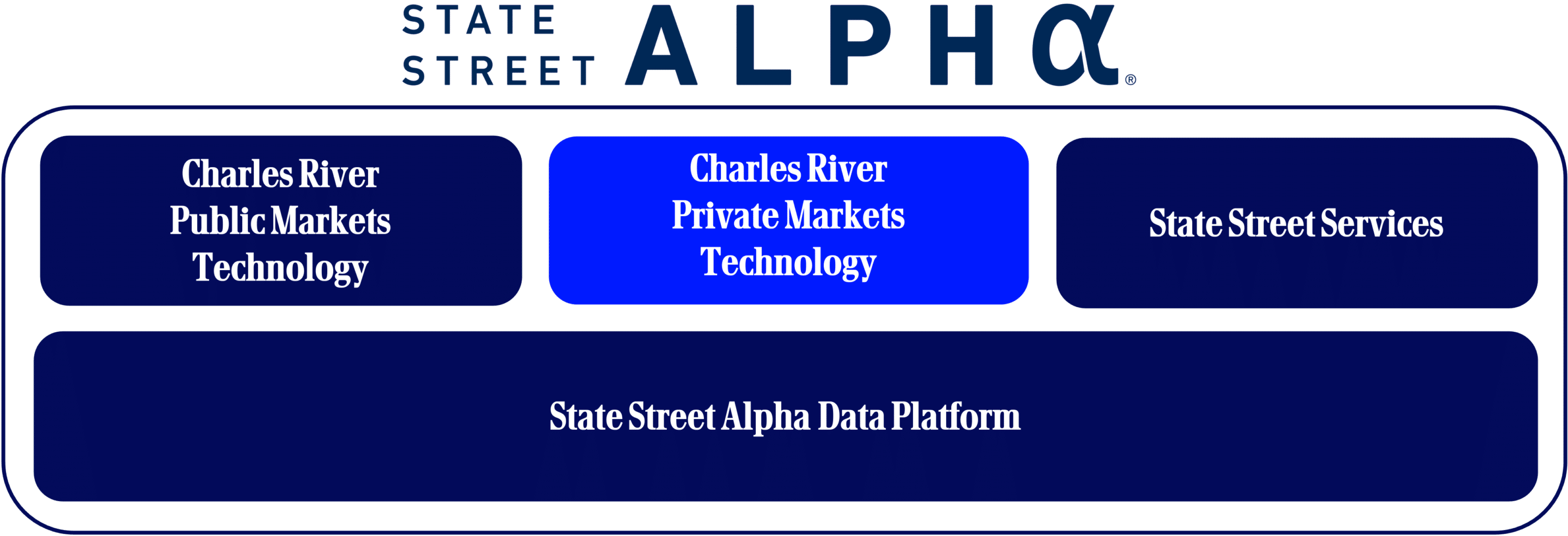

Charles River for Private Markets can meet you wherever you are on your data journey, whether you are investing in a single asset class and need a front office solution only, or if you are looking for a multi-asset, front-to-back office solution for your investment data. Our position within State Street enables us to provide a holistic solution with technology and services with State Street Alpha.

A Multi-Asset Solution in Private Markets

Asset managers and owners investing in different asset classes have different challenges with their data. We configure our solution to fit your needs, whether it’s in a single asset class or across multiple asset classes.

Private Credit

- Direct Lending, Mezzanine, Real Estate Debt, Infra Debt, Distressed, Specialty Finance

- Centralized borrower & loan data for effective monitoring

- Covenant tracking, streamlined unstructured borrower data collection

- Connected workflows across teams & departments

Real Estate

- Residential, Commercial, Mixed Use, Industrial, Office, Senior Housing

- Flexible system to invite brokers, property managers, asset managers, portfolio companies, and fund managers in single platform to facilitate data collection and workflow

- Track diverse assets at the most granular level and aggregate monthly cashflows

Private Equity & Funds

- Growth Capital, Buyout, Distressed

- Single solution for tracking the entire investment lifecycle, from deal to divestment

- Seamless connection between financial models and transactional data at the asset level

- Fund Secondaries, Fund of Funds, Asset Owners

Infrastructure

- Airports, Power, Transport, Water, Digital Infrastructure, Renewable Energy

- Purpose built for infrastructure assets and their complex, bespoke models

- Flexible data platform enables data collection and integration with multiple systems

- ModelSync technology connects all underlying models, enabling valuations at scale and fast forward-looking analysis across a portfolio

Want to learn more? Get in touch.

We're ready to answer your questions. Contact Sales & Marketing by filling out this form.

Follow us on our social channels to stay up-to-date on all Charles River News and Events.

Request a Demo to Learn More

Want to learn more? Get in touch.

We're ready to answer your questions. Contact Sales & Marketing by filling out this form.

Follow us on our social channels to stay up-to-date on all Charles River News and Events.